Understanding a Common Body Response and Its Role in Urinary Health!

In the intricate design of human physiology, many of our most vital protective measures occur without a single conscious thought. From the rapid blink of an eye to the reflexive stretch of a limb after a long period of stasis, the body is constantly engaged in a silent dialogue with its environment, sending signals intended to preserve equilibrium and defend against external threats. Because these responses are so seamless and automatic, they are frequently overlooked or dismissed as trivial occurrences. However, in the realm of urinary health, one of these subtle, routine behaviors—the urge to urinate following physical intimacy—serves as a critical biological safeguard. Understanding the mechanics of this response is essential for maintaining long-term comfort and preventing the common infections that can arise when these natural cues are ignored.

The human body operates through a sophisticated network of involuntary systems that manage everything from internal temperature to immune defense. Following periods of physical closeness and increased pelvic activity, the body undergoes a series of temporary physiological transitions. Blood circulation to the pelvic floor intensifies, muscle groups engage in cycles of contraction and relaxation, and hormonal levels shift to facilitate recovery and bonding. Within this context, the sudden sensation of needing to empty the bladder is not a random inconvenience or a disruption of the moment; rather, it is a highly evolved protective prompt. It is the body’s way of initiating a “rinse cycle” for the urinary tract, ensuring that the system returns to its baseline state of health and cleanliness.

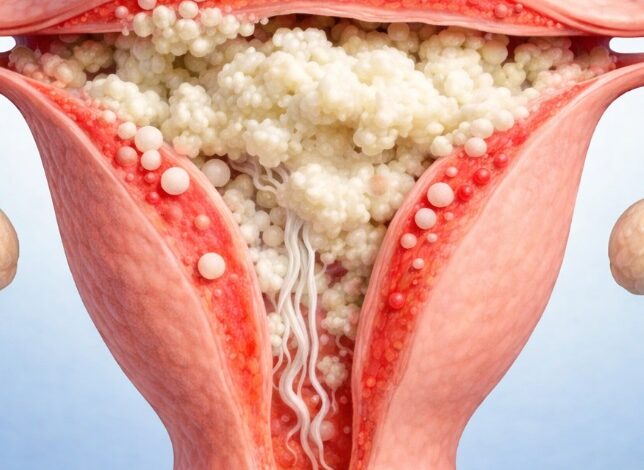

The anatomical proximity of the bladder to other pelvic organs explains why this sensation is so pervasive and predictable. During physical interaction, the movement and pressure in the pelvic region can provide gentle mechanical stimulation to the bladder wall. This stimulation activates neural pathways that communicate directly with the brain, signaling that it is time for the bladder to be cleared. Furthermore, physical arousal often triggers a temporary increase in kidney filtration rates, leading to a higher volume of urine production. When these physiological factors converge, the result is a natural, healthy urge that serves a significant medical purpose: the mechanical flushing of the urethra.

One of the most profound benefits of responding to this urge is the dramatic reduction in the risk of urinary tract infections (UTIs). These infections are typically caused when bacteria—most notably E. coli, which is naturally and harmlessly present in the digestive tract—migrate toward the urethral opening during physical contact. If these microorganisms are allowed to remain at the entry point or travel upward toward the bladder, they can attach to the sensitive lining of the urinary tract and begin to multiply. By urinating shortly after physical closeness, the body uses the outward flow of fluid to physically sweep these bacteria out of the system before they have the opportunity to colonize. This simple act of “natural cleansing” is one of the most effective ways to disrupt the infection cycle before it even begins.

While this protective mechanism is important for everyone, biological differences make it particularly vital for women. Due to a shorter urethra and its close proximity to other bacterial sources, the female anatomy provides a much shorter path for bacteria to reach the bladder. This inherent vulnerability does not mean that discomfort is inevitable, but it does underscore the importance of establishing proactive habits. Consistency is the key to prevention. By making post-intimacy urination a non-negotiable part of a personal wellness routine, individuals can significantly decrease their susceptibility to recurring infections and the long-term inflammation that often follows.

Beyond the prevention of bacterial overgrowth, the process of urination supports the general recovery of pelvic tissues. During periods of arousal, increased blood flow makes the surrounding tissues more resilient, but the friction and pressure of physical activity can still cause microscopic irritation. Urinating helps to clear away residual fluids and biological markers that could contribute to localized inflammation. It essentially assists the body in its transition back to a resting state, supporting tissue health and ensuring that the pelvic environment remains balanced and comfortable.

Some individuals may notice subtle changes in the appearance or scent of urine during this post-activity period. It is common for the urine to appear lighter in color or to possess a milder odor than usual. This is typically a sign of efficient kidney filtration and proper hydration, rather than a cause for concern. The most critical factor is the timing of the response. Postponing the urge to urinate—even for an hour—gives bacteria a “window of opportunity” to migrate further into the system. In people with certain underlying conditions, such as diabetes or a compromised immune system, even a short delay can significantly increase the risk of a persistent infection.

Establishing a comprehensive approach to urinary health requires looking beyond this single habit. Proper daily hydration is the foundation; by drinking adequate water, the kidneys are able to produce a consistent stream of urine that naturally cleanses the bladder throughout the day. Additionally, choosing breathable fabrics and avoiding harsh, scented hygiene products in sensitive areas helps to maintain the delicate microbiome of the pelvic region. When combined with the habit of urinating after physical contact, these practices create a robust, multi-layered defense system that protects the body from the inside out.

Despite its importance, discussions regarding urinary and reproductive functions are often clouded by a sense of embarrassment or cultural stigma. This silence frequently leads to misinformation and unnecessary anxiety about what are, in reality, perfectly normal bodily responses. Viewing the body as a high-performance system designed for self-protection helps to remove these barriers. Urinating after physical closeness is a shared human experience rooted in sound medical science. By acknowledging and respecting these automatic signals, we can replace confusion with confidence and foster an environment where self-care is prioritized over social awkwardness.

In the grand scheme of lifelong wellness, it is often the smallest, most accessible habits that yield the greatest rewards. Post-intimacy urination requires no specialized equipment, incurs no cost, and takes only a few moments of time. Yet, the long-term value of this practice—measured in the prevention of painful infections, the avoidance of antibiotic reliance, and the maintenance of daily comfort—is immense. Listening to the body’s signals is the ultimate act of self-care. When we understand the “why” behind our biological responses, we move closer to a lifestyle defined by informed decisions and sustained well-being. By embracing this natural protective cycle, individuals can navigate their lives with greater comfort, knowing they are working in harmony with a body that is always striving to protect itself.