This Simple Hand Gesture Holds a Surprising Meaning from the Past!

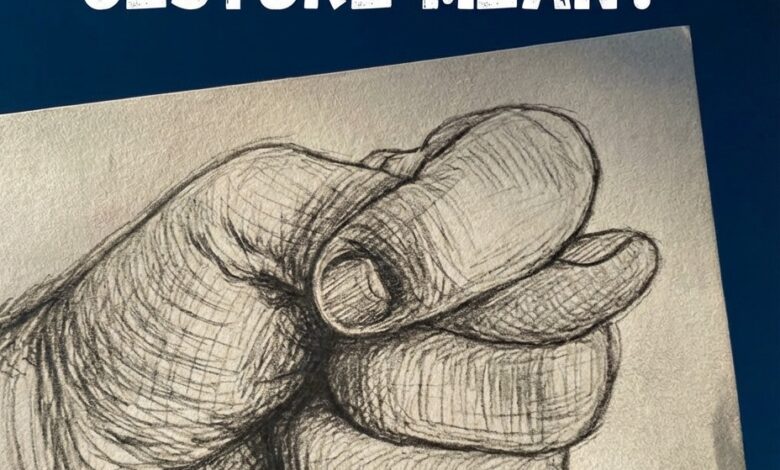

To the casual observer, it appears to be nothing more than a simple, clenched fist. But if you look closer, a subtle, deliberate detail emerges: the thumb is not wrapped around the exterior of the fingers, nor is it tucked beneath them in a standard grip. Instead, it is thrust firmly between the index and middle fingers, peeking through the knuckles. This small anatomical adjustment transforms an ordinary hand into an ancient and potent gesture known across various cultures as “making a fig,” or the mano fico.

Long before the advent of instant messaging, global telecommunications, or the standardized shorthand of emojis, this quiet sign served as a universal broadcast of human intent. It was a silent language that transcended borders, carrying a clear and unmistakable message with a single flick of the wrist. For centuries, the “fig” was a tool of the common person—a way to refuse an unreasonable demand, signal a hard-edged defiance, or succinctly communicate that something was “not happening” without the need for a single spoken syllable.

In the 19th-century villages of Europe, the gesture was far more than a simple insult; it was a sophisticated mechanism for social navigation. In a world where open conflict could lead to severe legal or physical consequences, the fig offered a vital middle ground. It allowed individuals to express resistance against overbearing authority figures, local bullies, or unfair requests while maintaining a layer of plausible deniability. To “show the fig” was to push back with a blend of humor, wit, and stubbornness. It was the ultimate “no” of the marginalized, a subtle middle finger to the status quo that kept the peace while preserving the user’s dignity.

Beyond its role as a social shield, the fig gesture was deeply steeped in the supernatural and the symbolic. In diverse folk traditions, the construction of the hand was seen as an architectural feat of spiritual protection. The closed fist represented a consolidation of hidden strength, a gathering of one’s personal power into a singular, impenetrable point. The tucked thumb, meanwhile, acted as a protective charm. It was widely believed throughout the Mediterranean and South America that making this gesture could ward off the “evil eye” (malocchio) or deflect the jealousy of neighbors. It was a physical amulet made of flesh and bone, a way to build a wall between oneself and the unseen forces of bad luck.

As the decades marched toward the modern era, the gesture’s sharpness softened, allowing it to move from the streets into the intimacy of everyday family life. It became a staple of intergenerational communication. Grandparents would pass the gesture down to children as a playful, lighthearted response to teasing or as a way to “steal” a child’s nose in a game of pretend. Even in these domestic settings, however, the root of the gesture remained the same: it was a lesson in standing one’s ground. It taught the younger generation that they had the right to set boundaries, even if those boundaries were expressed through a wink and a closed hand.

For some, the gesture carried even deeper emotional resonances. It appeared in the quiet, heavy moments of human transition—during the uncertainty of a long-distance separation or the internal gathering of courage before a daunting challenge. In these contexts, the fig was less about defiance and more about quiet resolve. It was a way for a person to tell themselves, “I am solid, I am protected, and I will not be moved.” It offered a sense of somatic comfort, a physical grounding that could steady a racing heart during life’s most difficult trials.

In our contemporary landscape, the sight of someone “making a fig” has become increasingly rare. We live in an era of digital saturation, where the nuanced, tactile language of the body has been largely replaced by the sterile precision of the screen. We express our defiance with block text, our humor with GIFs, and our protection with cybersecurity software. The physical vocabulary of our ancestors is fading into the archives of anthropology, replaced by a globalized set of icons that, while efficient, often lack the visceral weight of a hand-formed sign.

Yet, despite its disappearing visibility, the inherent meaning of the fig gesture has not vanished; it has merely migrated. The human impulse to communicate strength, boundaries, and protection remains as vital as ever. The history of the fig serves as a powerful reminder that the most profound messages don’t always require a megaphone or a high-speed connection. Sometimes, subtlety is the most effective form of communication. Sometimes, humor is the strongest armor.

The fig gesture stands as a testament to human ingenuity in the face of silence. It reminds us that we have always found ways to speak truth to power, to protect our loved ones, and to define our own space in the world using nothing more than what we were born with. It is a legacy of wit over volume, proving that a single, well-placed thumb can speak as loudly as a thousand words. Even as we move further into a world dominated by virtual signals, the “fig” remains a symbol of the enduring power of the human touch—a quiet, clenched fist that continues to echo the defiance and resilience of the past.